Legacies of Empire

National War Museum

*This blog post, like all of the content on this website, is representative of my own personal views and not those of my employers*

I was thrilled when I found out that the ‘Legacies of Empire’ exhibition at Edinburgh’s National War Museum had been extended. Enormous hype and clever PR had promised a ground-breaking exhibition that challenged the dark colonial histories of some of Scotland’s extensive museum collections, and for me, it was an absolute must-see.

Surprisingly, ‘Legacies of Empire’ was a first in Scotland. The glaring history of violent imperialism that is entwined in every fibre of Scottish heritage, and nowhere more so than in the nation’s world-class collections, had never been directly addressed in a Scottish exhibition before. And where better to start the conversation than the National War Museum in Edinburgh Castle, an impressive historic display of Scotland’s military history situated in one of the country’s most significant tourist attractions. Needless to say, I was pretty excited.

“The glaring history of violent imperialism that is entwined in every fibre of Scottish heritage… had never been directly addressed in a Scottish exhibition before”

The exhibition introduces the fact that most national and military museums are filled with objects that were “taken, purchased, or otherwise collected” by Britons across the empire. The subdued wording here was a bit of a red flag for me, but I was keen to see what the exhibits had to say. The first room is broken down into two themes: ‘loot and prize’ and ‘trophies’. The wall colour is a light sage green; an interestingly neutral choice of colour that actively seeks to calm emotions and mellow the atmosphere.

To give an example of the space, the ‘loot and prize’ case contained around 10 objects, and began by talking about imperial looting in a very matter-of-fact way. One object told the story of a decorative silver club that belonged to Kunwar Singh that was taken by General Godfrey Pearse during the Indian Uprising (here I noted the very conscious choice to use the word ‘uprising’ rather than the more incendiary ‘mutiny’, which is how the conflict is usually described – in contemporary India, it is often referred to as the First War of Indian Independence, despite the fact that Indian and modern Pakistan were fractious states, kingdoms, and empires, rather than a united ‘India’ – sepoys of the East India Company’s Presidency Armies rebelled against British military leadership, protesting the interference in and lack of respect for Indian culture, social structures, and religions. This phrasing was clearly one step too radical for National Museums Scotland).

Reading the label, I was surprised at how ‘unapologetic’ it seemed – the idea of Britain getting down on its knees and begging for forgiveness from the countries that it ruthlessly pillaged and brutally colonised is not a popular one (although I personally believe that this is entirely necessary), but a bit of humility wouldn’t have gone amiss here. The object described as ‘rich spoils’ suggests no future actions and addresses none of the personal or cultural repercussions of looting.

Stripped back to only the facts, the first room provided a clinical overview of the simple case that the British used their empire as a breadbasket from which they could loot, pillage, and collect with absolutely no repercussions.

Meandering on to the next room, I was confronted by three more themes: ‘collectors’, ‘relics, mementos and memorials’, and ‘allies, gifts and trades’. This section focussed more on the ‘legitimate’ acquisitions of Britons in empire through the means of trading and purchasing, and collecting discarded objects from battlefields as personal mementos with very little immediate value.

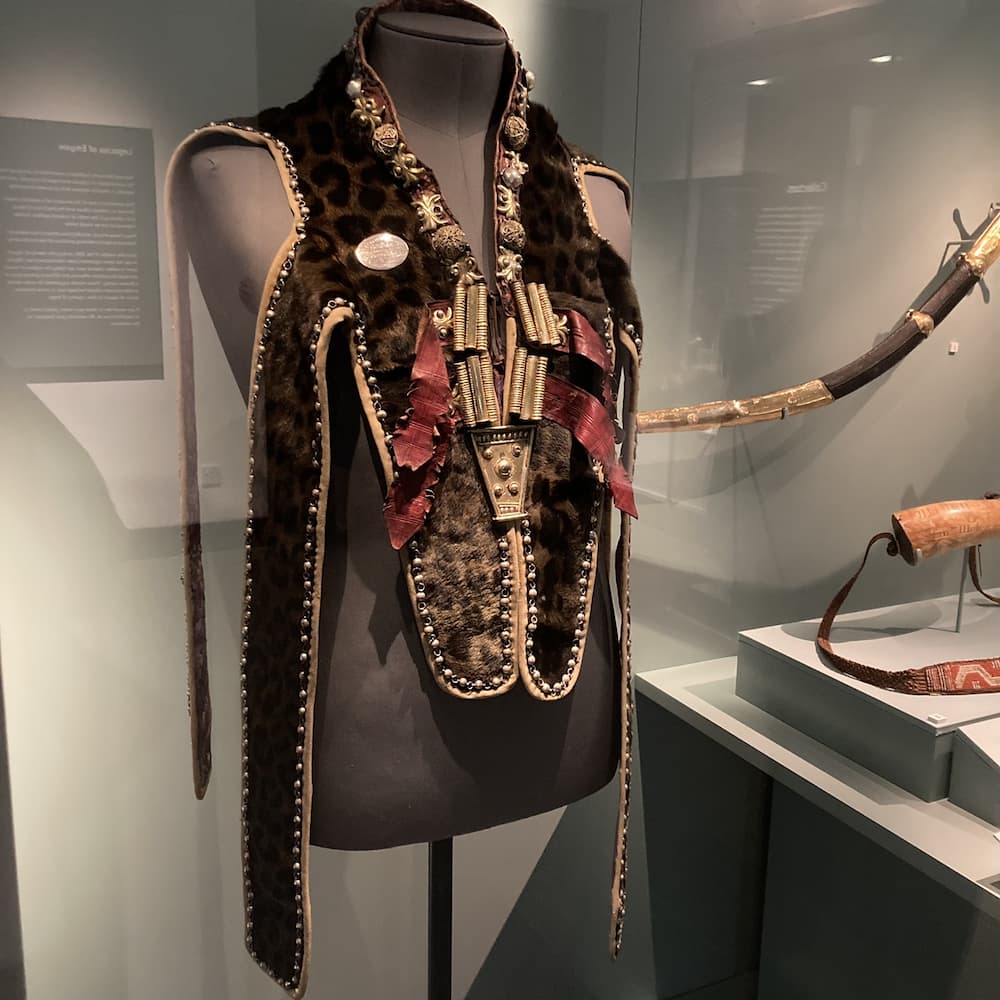

One interesting object was a leopard skin cape that was apparently given to the British Indian Army officer Robert Napier (also known as the 1st Baron Napier of Magdala) during the Abyssinia Expedition in 1868. The expedition was a rescue mission to relieve missionaries and British diplomats who had been taken hostage by Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, presumably because he opposed the ethically questionable intentions of foreign Protestant missionaries.

The label tells two conflicting stories: one, that the cape was supposedly gifted by Dejazmatch Kassa Abba Bezbez to Napier as a symbol of good diplomatic relations as Napier crossed Kassa’s territory to locate Tewodros II. And two, that it was looted from Tewodros II’s palace during the siege of Maqdala, and was gifted by the British government to Napier following a successful mission. I think I know which story is more likely to be true, and I was left wondering why National Museums Scotland (NMS) felt it was necessary to perpetuate both as equally likely to be true.

“Museums should be inherently woke spaces, working tirelessly to make amends … for the historic rape of colonised countries”

This room made an important contribution to portraying the whole story of colonial collections – there were undoubtedly legitimate dealings, and the explanation of taking low-value battlefield mementos for memorial purposes was an interesting addition. Keen to see how the exhibition would address the actual, modern legacies of empire (that is to say, the emotional impact on the modern-day viewer of these objects, what can be done about half-baked interpretations of colonial collections, and the ever-pressing question of repatriation), I pressed on. Following the lead of the exhibition space, I turned the corner only to find… that the exhibition was over. That was it. The blockbuster, narrative-challenging, perspective-flipping exhibition that promised a candid look at Scotland’s colonial history… was two small rooms, a handful of semi-interpreted objects, and some painfully unchallenging text panels.

I circled the exhibition again, just to make sure I wasn’t missing a discreet passageway or subtle door. I wasn’t. Trying to understand the position of NMS, I can see that this exhibition is a first step in confronting Britain’s role in empire and its material legacy. Positioned in a war museum, it takes a gentle, unchallenging, and even neutral stance when addressing these powerful topics, demonstrating the museum’s trepidation: the fear of upsetting visitors, lenders, and trustees with an overly ‘woke’ exhibition appeared to be off the cards. God forbid a museum might rattle the cage and question the glory of Britain with too much fervour. It’s 2022. Museums should be inherently woke spaces, working tirelessly to make amends (which isn’t really possible but no one ever seems to have tried) for the historic rape of colonised countries.

Exhibitions like ‘Legacies of Empire’ make a start, and I accept and appreciate that they are trying. But there is a very real risk that weak and cowardly analyses of this legacy are further damaging an already fractured process. I couldn’t help feeling disappointed by this exhibition, but I am encouraged that NMS at least tried. ‘Legacies of Empire’ is a very small step in the long journey towards addressing Britain’s violent colonial history, and I commend them for making a start. I just wish it was better.