All Too Human: Bacon, Freud, and a Century of Painting Life

Tate Britain

£11.00 – £25.00

28/2/18 – 27/8/18

London, UK

8 / 10

Normally I start an exhibition review with a summary of the themes, works and artists involved in an exhibition, but this time it’s a little more difficult. It seemed like the curator had an idea of a few key artists, namely Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, and wanted to bring them together in an exhibition which explored modern expression of the human form. All the other artists involved turned this theme into a group of roughly London-based artists, from a period of over a hundred years, who all, at some point, painted “life”. The initial concept seemed a bit of a jumble, but at the same time it made for a diverse and varied collection which didn’t leave me feeling overwhelmed by just one artist and style.

“‘Study after Velazquez’, captivated and simultaneously repulsed the audience”

The exhibition has a typical, chronological layout and the pale grey wall colour, which continues throughout the exhibition, is a modern and neutral choice which really enhances the works on display. The first room displays the earliest artists such as David Bloomberg and Stanley Spencer. In particular, Spencer’s work inspired modern artists in terms of paint handling and subject matter. One of my favourite works from this room was Chaim Soutine’s ‘Polish Woman’, c.1922. I wasn’t familiar with her work before the exhibition, but the impasto application of paint in garish oranges, purples and blues creates an intriguing, distorted figure which narrates the sitter as well as the artist.

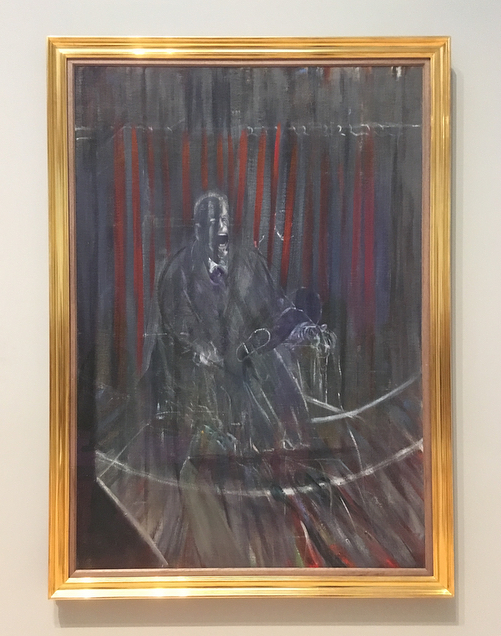

Room 2 is where we are introduced to Bacon and Giacometti. To quote the wall panel, Bacon’s “isolated, angst-ridden figures” dominate the room. His ‘Study after Velazquez’, 1905, captivated and simultaneously repulsed the audience – the composition echoes Velazquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X, but instead of the Pope, we see a screaming man, creating an atmosphere of distress and confinement. The elongated streaks of purple and red heighten tension and emotion, and the rough use of line is almost insanity-inducing. Most of the detail is centred around the open, screaming mouth. The horror associated with the agonised white teeth and pink lips captivated everyone who passed through the room and compelled them to stare. It is a painting full of raw emotion which reveals pure terror, uncertainty and despair.

“I painted ‘Negro in Mourning in London when the race riots flared. [It] is close to the bone of man because it is about the colour of skin” – F N Souza

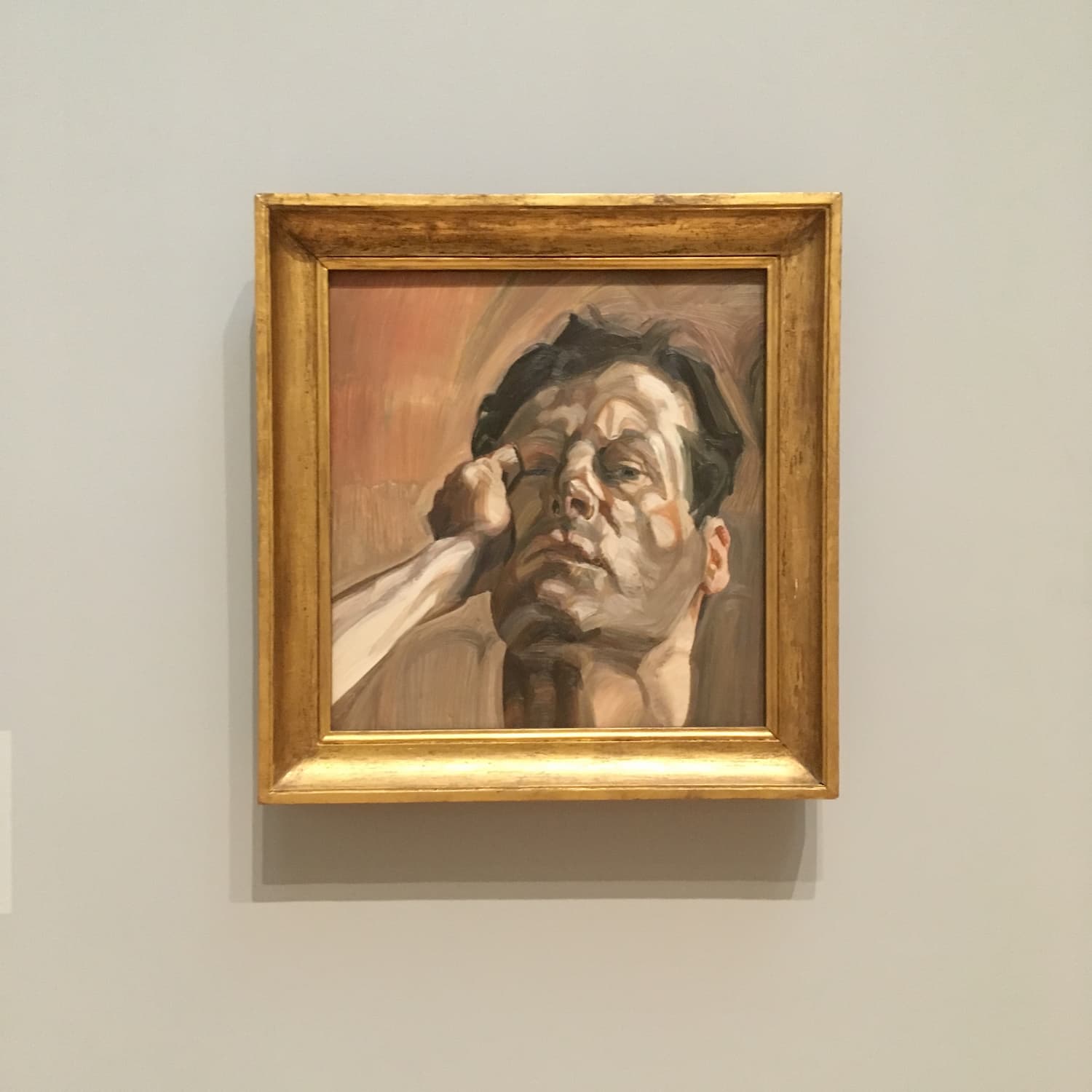

“He captures a form of beauty, but chooses to express a heightened reality”

The artist explores all types of people, from clunky and curvaceous to skeletal and emaciated. He captures a form of beauty but chooses to express a heightened reality through large brushstrokes and the haunting effect of light and shadow. He was one of the first twentieth century Britons to depict the human form in its reality, instead of idealised beauty. This is very clear in the painting ‘Sleeping by the Lion Carpet’, 1996, which shows one of his regular models known as Big Sue; the contrast to the traditions of the female nude are obvious, and this paved the way for Freud’s distinctive style: unforgiving subject matter and self-assured paint application.

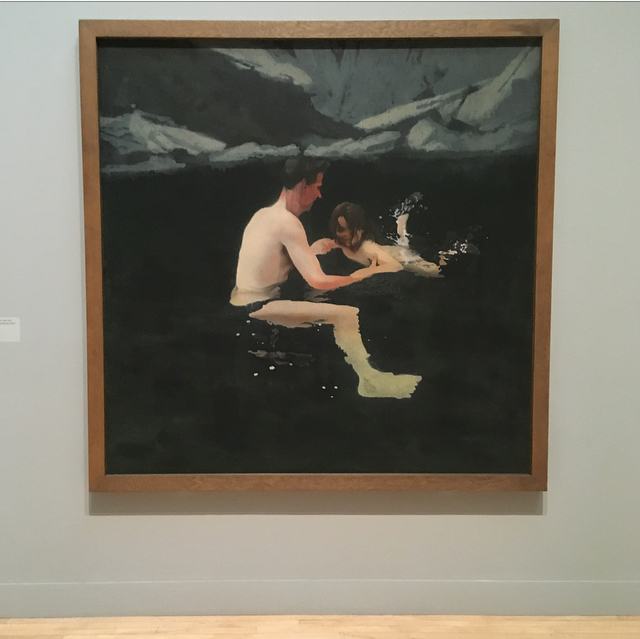

Michael Andrews was a leading British painter in the post-war period, but I had never heard of him work before visiting the exhibition. Some of his works were my favourite of the whole show. His work ‘The Deer Park’, 1962 is surreally reminiscent of Manet’s ‘Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe’, 1862, with bourgeoisie subjects, and earthy yet elegant tones of green, brown and blue. Andrews’ painting ‘Melanie and Me Swimming’, 1978-9 was a visual delight. It’s simple shapes, planes of colour and heart-warming subject matter made this a stand out piece for me. The interaction between the artist and his daughter is very distinctive, and the style stood from the exhibition. The original photograph from which Andrews worked was also included in a display case of artists’ letters and images from their studios, which was at the end of the show; for me, this brought it all together and was a valuable contribution to the whole exhibition.

“Despite being almost grotesque, the painting is unarguably beautiful”

Jenny Saville is one of the most famous, contemporary names in the exhibition, and I was very excited to see her work: there was only one of her paintings, but it didn’t disappoint! ‘Reverse’, 2002-3, is a classic example of her work. A self-portrait, she is depicted side on, bloodied and bruised. Her lip is swollen, and the huge, expressive brushstrokes depicts her facial contours in surprising detail. It is as though she is lying on a glass table, or a mirror, and the reflection adds a depth and realism to the work. The canvas is huge, and despite being almost grotesque, the painting is unarguably beautiful.

In the same room, we are introduced to the work of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Her paintings are modern and real, with thick and fast application of paint which captures a moment in time. Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings are produced in just a day, and her subjects are imaginary. This gives her works an extra layer of intrigue, and as well as being visually enticing, they are a fascinating exploration of the artist herself.

I really enjoyed this exhibition. It flowed well, and the chronology made it easy to follow throughout. The enormous period of artists which the exhibition covered could be seen as a bit of a random selection, but the exploration of humanity in its many forms is a fascinating story to follow. At times, the wall text is a little over-complicated which I think can be exclusive and isolating for more casual viewers, and more information on gallery labels wouldn’t go amiss. But this exhibition is visually exciting, and opens up artists, artworks and styles that you wouldn’t hear much about otherwise, which is great! Unfortunately, the exhibition is now closed, but a solo exhibition of any of the artists involved would be great to look out for, and